I use this blog almost exclusively to chat about knitting-related topics. But every once in a while, I need to veer off course a bit.

For those of you who do not know, I work at various careers in addition to knitwear designing. One of the hats I wear is that of an adjunct professor of Italian literature. Through this current pandemic crisis, I’ve kept in close contact with my friends in Italy, and I’ve kept a constant eye on the news coming out of Bergamo, the area most severely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. And in the past two weeks, which have already felt like a lifetime, I have noticed something in particular.

The references to Boccaccio’s Decameron began almost immediately. At first, they were quaint, almost cutesy. “It’s like we’re reliving one of our great works of literature! Let’s have a Decameron party!” Live readings of the Decameron sprung up everywhere. Reconnecting with the past created a sense of community, of shared history, and maybe it made a little light of a situation no one yet dreamed would become a total nightmare. In just a matter of days, as the reality of the pandemic set in, all readings of and references to the Decameron would abruptly stop.

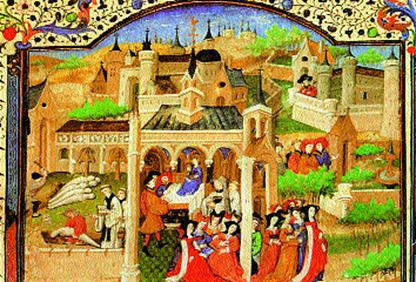

For those of you unfamiliar with this great work of the Italian canon, the Decameron is set in Florence, Italy, in the year 1348 – the year in which the Black Plague swept across Europe, leaving decimation in its wake. Giovanni Boccaccio, the author, survived the plague, but not without great loss, including his close friends and family, as we know from epistolary exchanges during that time. In the introduction to his Decameron, he sets the scene with a vivid and horrifying description of plague-ravaged Florence, one of the most comprehensive and accurate historiographic accounts we have today. Amid the death and chaos, ten young people escape the city and take refuge together in the countryside, each telling ten tales over the course of ten days to pass the time, for a total of one hundred tales. They range from humorous to tragic to downright bawdy, all still just as entertaining today as they were centuries ago.

Boccaccio’s account of the Black Plague is eerily similar to our own situation today. In the period stretching from early spring into July, he tells us:

the pestilence, originating some years earlier in the East, killed an infinite number of people as it spread relentlessly from one place to another until finally it had stretched its miserable length all over the West. And against this pestilence no human wisdom or foresight was of any avail; quantities of filth were removed from the city by officials charged with the task; the entry of any sick person into the city was prohibited; and many directives were issued concerning the maintenance of good health.

He explains how the disease was transmitted not only from the sick to the healthy, but also from the clothing and belongings of the dead or dying to those tasked with discarding those items.

Not surprisingly, the reactions of the city folk mirror what we are witnessing today as well. Some took the situation very seriously, and “shut themselves up in their houses where there were no sick people and where one could live well by eating the most delicate of foods and drinking the finest of wines…” Others, of course, took no heed of their own health or that of others:

they believed that drinking excessively, enjoying life, going about singing and celebrating, satisfying in every way the appetites as best one could, laughing, and making light of everything that happened was the best medicine for the disease; so they practiced to the fullest what they believed by going from one tavern to another all day and night, drinking to excess; and they would often make merry in private homes, doing everything that pleased or amused them the most. This they were able to do easily, for everyone felt he was doomed to die and, as a result, abandoned his property, so that most of the houses had become common property, and any stranger who came upon them used them as if he were their rightful owner.

And then, of course, there were those, “caring only about themselves,” who decided to flee the city and unwittingly carry the disease into all areas of the countryside – “as if the wrath of God could not pursue them with this pestilence wherever they went,” quips Boccaccio with grim sarcasm.

What seems most disconcerting in this account, both to Boccaccio as author and to us as the reader, is the complete collapse of the social order. Everything is tipped on its head; people are partying in the houses of the dead; mothers are refusing to go near their dying children; farmers are dropping dead where they stand in the fields; crops are withering on the vine; with all sense of law and order crumbling, anarchy prevails in the cities; price-gouging becomes the norm, and the wealthy are shelling out their life savings for basic necessities or health care, while the poor simply die in the streets.

It’s a horrifying thought. Horrifying then, horrifying now. And yet, even with chaos at the reins, even with all semblance of normalcy erased, even with half the city’s population gone, order did return. We know this, because we can witness the historical artifact of this truth. Very quickly, life returned to the city. Authors like Boccaccio were able to return to their work, artisans plied their trades, the crops were resown. Within fifty years of the plague, Florence became the birthplace of an artistic and cultural renaissance for which it would be celebrated into the present era. Order would once again prevail.

Here is Boccaccio’s point, upon which he insists throughout this collection of tales: we can re-establish order after complete chaos. In fact, it is our duty to do so. But we cannot expect our society to look exactly as it did before the crisis. It would be foolish even to imagine that we can just pick up and start where we left off. And it is simply unreasonable to imagine we can continue to perform our duties now, in the midst of the crisis, just as we did before the outbreak. For those of you struggling to teach your children at home while working full time, Boccaccio would scoff at the inconceivability of it all. For those of you struggling with new-to-you technology for virtual meetings and distance learning, give yourselves a break. Drop those expectations down a notch.

Boccaccio instead advocates for the path of moderation – no extremes on either end. We need to loosen our rigorous hold on social norms, and maybe even on propriety, but not to the extent that we fall into the clutches of chaos and inhumanity.

And most importantly – this, indeed, is his whole purpose in writing his collection of tales – we need to find reasons to smile. A sense of community is paramount right now. We NEED each other in order to keep our heads above water. This is so difficult in a time of social distancing, but it can be done. Share on social media. Reach out to one another virtually. Share information. Make each other laugh. Hold your family close. Have faith that our society will still exist on the other side of the tunnel. It won’t look quite like it does today, and maybe that’s not such a bad thing. We’ll have a chance for rebirth. Remember what is truly important when that time comes.

*All quotes from the Decameron are taken from Musa and Bondanella’s translation. Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron. Trans. Mark Musa and Bondanella. Intr. Thomas C. Bergin. New York: Signet, 2002.

Leave a Reply